Edouard Léon Théodore Mesens (1903-1971) was Magritte's friend, his brother Paul's piano teacher and one of the central figures of surrealism in Belgium and London. He was certainly one of the most important people in Rene Magritte's career.

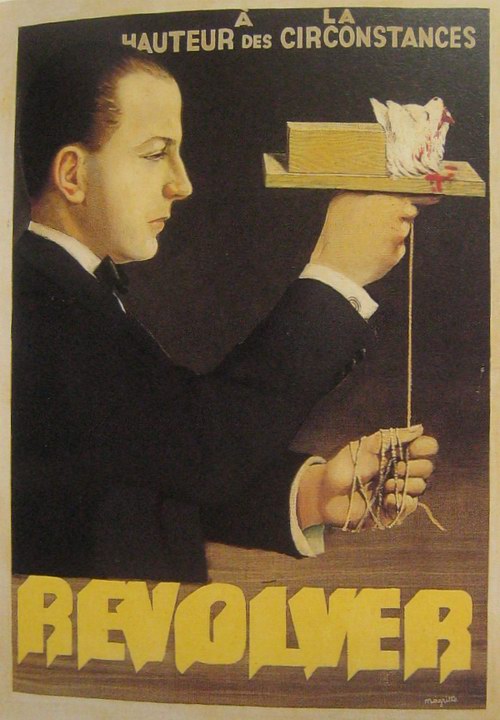

Portrait of ELT Mesens 1930

Magritte met Mesens in 1920 when ELT was an aspiring pianist and composer. Here's an excellent article on E.L.T. Mesens who was Magritte's sponsor and friend:

Online Magazine of the Visual Narrative

Issue 13. The Forgotten Surrealists: Belgian Surrealism Since 1924

E.L.T. Mesens - Dada Joker in the Surrealist Pack

Author: Neil Matheson

Published: November 2005

Abstract (E): This article analyses the work of the Belgian surrealist E.L.T. Mesens in relation to his deeply entrenched commitment to Dadaism. Although a fervent surrealist, Mesens nonetheless remained marked by his early involvement in the Dada movement, through his contact with figures like Tristan Tzara , Man Ray and Francis Picabia. The author argues that, even after the formation of the Belgian surrealist group in 1926, Dada continued to inform Mesens' attitudes and working practice and that, in fact, for Mesens, Dada remained a lifelong influence. Mesens' surrealism was thus permeated by his subversive humour, combative attitude, and by the visual and typographic styles associated with the Dada movement.

What is Surrealism?

- It's relearning to read in the alphabet of stars of E.L.T. Mesens.

André Breton (1934) [1]

E.L.T. Mesens: Le plus Bruxellois des citoyens du monde

An undervalued figure - at least in England - Edouard Léon Théodore Mesens (1903-1971) played a crucial part in the early development of Belgian surrealism, acted as a pivotal figure in relations between the Brussels and Paris groups, and had an important role in the extension of the movement to Britain in 1936, eventually becoming leader of the Surrealist Group in England. As a curator, occasional poet, publisher, editor, and - in a late flourishing of his work as a creator - producer of collages, Mesens spanned the whole range of surrealist activity. For David Sylvester, less convinced of his talents as a creator, Mesens was 'not so much versatile as dilettantish' (Sylvester 59), whereas for his biographer, Christiane Geurts-Krauss, Mesens is "l'alchimiste méconnu du surréalisme " - an unjustly neglected figure who worked tirelessly to promote those artists such as Magritte, whose work he admired (Geurts-Krauss 13). For his friend, the writer and fellow surrealist, Louis Scutenaire, Mesens was the link between the surrealist groups of Paris and Brussels, "smoothing out difficulties - or creating them when need be!" (Scutenaire 9). Scutenaire observes that Mesens was turned more to the external world than were his Belgian colleagues, while at the same time deeply proud of his Brussels roots - a view echoed by his mentor and friend, the gallerist Paul-Gustave Van Hecke: "He's the most 'Brussels' of the citizens of the world that I know" (Van Hecke n.p) [2].

Mesens was born in the old quarter of Saint-Géry in Brussels, geographical roots of which he was always proud, and near which was a café where in 1911, the anarchist Bonnot gang would meet. Mesens famously wrote in 1944 : "I was born on the 27 November 1903, without god, without master, without king and without rights" (Mesens 1944) [3]. This credo, often repeated in Mesens' many catalogues, recalls the opening of Max Ernst's 'Biographical Notes': "On 2 April in the small town of Brühl, not far from the sacred city of Cologne, he opened his eyes", (Ernst 281) and Ernst was to be an enduring influence upon Mesens' collages. A talented (though somewhat lazy) pianist, Mesens at first seemed destined for a career in music, where the work of Satie came to him as a revelation, and of whom he observed: "Thanks to the work of Satie my first personal revolution was accomplished. Goodbye sentimental love of the Flemish land; goodbye impressionist harmonies; goodbye schmaltzy humanitarian poets!" (Otlet-Moutoy 175) [4]. Mesens abandoned music in 1923, curiously citing "moral" reasons, though this sounds suspiciously like Mesens aligning himself with Breton's prejudice against music, whereas the English surrealist George Melly points out that Mesens admitted lacking the "mathematical" aptitude, and that on a more practical level, his father refused to fund his musical studies (Melly 1971: 24). With typical self-assurance Mesens introduced himself to Erik Satie, in April 1921, when the latter was performing in Brussels and made his first trip to Paris with Satie in December of that year. Satie, a humorist and poet as well as a composer, introduced Mesens into Dadaist circles, where he met Tristan Tzara, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes and Philippe Soupault, and lunched in Brancusi's studio with Marcel Duchamp; he also met Man Ray and went along to the latter's first Paris exhibition at the Galerie Six (Mesens 1979: 12). Mesens later described Satie as "a sort of anarchist" and Mesens' own tastes were more for Dada irreverence and revolt, than for early surrealism (Geurts-Krauss 33).

Still only in his late teens, Mesens was deeply marked by these early contacts with Paris Dada, taking from Tzara his cosmopolitanism and dandyism, and from Picabia the role of bon viveur and raconteur, as well as a love of eroticism, intrigue and scandal. For Melly, who knew Mesens intimately, Mesens was "a mass of contradictions": "He was a monster but a sacred one. An angel but fallen" (Melly 1971: 23). Although, as he himself affirmed, "surrealist to his fingertips", I want to insist on the enduring impact of Dada on Mesens' work and attitudes. As David Willinger argues: "There is no question of regarding Dada in Belgium as having been a movement per se. It is more accurate there to speak of the Dada spirit ." (Willinger 2). Dada sprang up spontaneously in Belgium and was championed, with little support, by Clément Pansaers, founder of the review Résurrection (1917-18). First learning of Dada while in Berlin in 1919, Pansaers went on to Paris where he participated in Paris Dada, eventually returning to Brussels disillusioned in 1922, where he died soon after of Hodgkin's disease. According to José Vovelle, of the future Belgian surrealists, only Marcel Lecomte had direct contact with Pansaers, though Dada left no significant trace upon his subsequent work (Vovelle 14). The Dada label could also be extended to the Antwerp artist Paul Joostens, and perhaps to the work of Michel Seuphor, though there was nothing at all comparable to the Paris Dada movement that Mesens encountered in his early trips to that city (See Sauwen).

Many commentators have noted a strongly Dadaist flavour to Mesens' humour, his most enduring acquisition from Satie. Melly relates a tale of Mesens and friends, in Brussels, who "pissed from the balcony during the premiere of a patriotic symphony (Melly 1997: 20)." Melly also describes Mesens, during the war, making elaborate diversions through Soho, to the exposed toilet of a bombed house, where he would "solemnly urinate - a gesture", Melly says, "both Dada, surrealist and, especially, Belgian" (Melly 1997: 21). During the early 1920s Mesens contributed to a number of avant-garde reviews (Ça Ira, Créer), including the Dada-oriented Mécano edited by Theo van Doesburg, which made the fruitful connection between Dada and Constructivism. It was through the intervention of van Doesburg that Mesens first met Kurt Schwitters, in Paris, further reinforcing the impact of Dada upon the young Mesens. Mesens, together with Magritte, then made detailed plans during the latter part of 1924, for the launch of a Dada review, Période, with the collaboration of Tzara. During a period of growing tension between the Dada movement in Paris and Breton's Littérature group, Tzara had attempted in July 1923 to re-launch Dada with his theatrical piece Le Coeur à Gaz, only to see the event violently disrupted by Breton and his friends. Mesens, though, with his love of music, (in marked contrast with Breton's vaunted aversion - "So may night continue to descend upon the orchestra") (Breton 1) and with a strong taste for subversion, found Tzara a powerfully attractive figure, and in August 1923 launched a long correspondence with him which endured until 1926. In their letters we find the two men making what were eventually to prove abortive plans for a Dada lecture tour of Belgium by Tzara and for a ballet, as well as organising various literary collaborations. Pansaers' plans for a Dada soirée in Brussels had come to nothing and it would appear that Mesens had similar ambitions for a Dada-inspired event in Belgium, centred upon the involvement of Tzara, which were likewise eventually to be frustrated (Massonet 16-28). We also find Mesens criticising Breton's collection of essays Les Pas Perdus, which appeared early in 1924, and which contains a number of important attacks on Dada and on Tzara in particular (Massonet 34-7 and 42-4).

Mesens, together with Magritte, also contributed what David Sylvester rightly judges to be rather feeble aphorisms to the final issue of Picabia's Dada review 391 (October 1924) - more significant was that Picabia used the issue to launch a spoof movement, Instantanéisme, as an attack on the newly formed surrealist movement (Picabia 127). The first Manifeste du surréalisme was published on October 15 1924 and Mesens was therefore associated with this half-hearted, Dadaist attempt to spike the guns of the new movement. Writing in October 1924, Mesens informs Tzara that he will soon have a theatre available in Brussels, where he intends to stage various events , including Tzara's Mouchoir de Nuages, raising the intriguing possibility of a late flourishing of Dada in Belgium (Massonet 43-4). In the event, Mesens' Dada spirit was to find expression in Période, produced together with Magritte, which eventually appeared in March 1925 under the new title Osophage, following a split with Goemans and Lecomte, initiated by Paul Nougé (Nougé subtly undermined Mesens' plans by issuing a pastiche of the prospectus that Mesens had issued for Période) . The review, with its device Hop-là, Hop-là, was in a distinctly Dadaist spirit, its contributors including Arp, Ernst, Picabia, Schwitters, Ribemont-Dessaignes, Pierre de Massot and the Dutch Dadaist I.K. Bonset (Theo van Doesburg). Launched in typical Dada style, at Tzara's request the review included the last-minute addition of an inflammatory open letter "of a rare violence", relating to the latter's running dispute with André Germain, and which Tzara promised would "launch your review with a ringing scandal" (Massonet 83) [5]. On the front cover, in their 'Les 5 Commandements', Mesens and Magritte claimed a politics of 'autodestruction' and an absolute refusal to explain, while Tzara declared that: "Shit is realism, Surrealism is the smell of shit" (Mesens and Magritte 1) [6].

The following year saw the launch of Marie - Journal Bimensuel pour la Belle Jeunesse, a review that, in its playful, subversive tone, typographic play and choice of contributors, was firmly in the Dadaist tradition. The second, double, issue (8 July 1926) featured Picabia's Optophone on its cover - a 'target' of concentric circles, with the sex of a reclining woman at its heart - together with Dadaists such as Tzara and Ribemont-Dessaignes, and was clearly something of an anachronism coming so long after the fading of Dada elsewhere in Europe.

Paul Nougé, however, famously "vomitted Dada", and with the merging of Mesens and Magritte with the Correspondance group towards the end of 1926, Nougé assumed the leadership of the nascent surrealist group; Mesens' role was correspondingly reduced and the Dada influence was replaced by that of Parisian surrealism. Breton, Eluard and Morise had visited Nougé in Brussels in the summer of 1925 and, as a theorist and intellectual, he was clearly perceived by the Parisians as the leading figure of the Belgian group. The final issue of Marie - Adieu à Marie - therefore assumed a very different character, less Dadaist in tone, and rather closer to surrealism. As a purely Belgian, francophone production it marked a shift from the Dada cosmopolitanism of the previous issue and was more concerned with establishing a cohesive Belgian group. While the review also looks more serious, it nonetheless retains an air of Dadaist provocation, with Mesens staging a powerful pairing of images of menacing clenched fists (Comme ils l'entendent, et comme nous l'entendons, 1926) , photographed by Roland de Smet, using a simple process of inversion, where the same object, a knuckle-duster, is simply inverted. The result is a rather brutal and somewhat anarchistic message, further reinforced by Nougé's poem 'les syllables muettes', which begins: "Our mouth is full of blood. Our ears ring with blood. Our eyes light up with blood." [7] In combination, then, images and text work together to create an air of unspecified violence and menace. While concurring with other commentators that, with his absorption into the nascent Belgian surrealist movement in 1926, Mesens finally abandons his plans for a revival of the Dada movement in Belgium, I would nonetheless argue that Dada retains its grip upon Mesens, and that we can trace such influence in his activities as gallerist and picture editor, as well as in Mesens' own collages.

[photo]

Fig.1 Goemans, Miró, Arp, Mesens (behind) and van Hecke in a pastiche of Ernst's Au rendez-vous des amis (1922), Variétés, June 1928.

In January 1927 Mesens was named director of the gallery L'Epoque by Van Hecke, who went on in March 1928 to launch the cultural review Variétés (1928-30), modelled on the German review Der Querschnitt. Mesens is credited by Jacques Brunius with a significant role in the selection and layout of images in Variétés (De Croës and Lebeer 301) , making heavy use of photographs, and the review also reflects Mesens' personal tastes - the issue of December 1929, for example, has a particularly strong Dada flavour, with a short play by Ribemont-Dessaignes, poems by Mesens and Tzara, collages by Ernst and absurdist drawings by Marc Eemans. In the June 1928 issue, Mesens appears in a group photograph taken at the recent Arp exhibition, standing behind Arp, together with Miró, Goemans and Van Hecke (fig. 1). The image is juxtaposed against Ernst's Au rendez-vous des amis, an iconic Dada work dating from 1922 which brought together Dadaists and members of Breton's Littérature group. Arp figures in both the photograph and the painting, with his seated pose echoing that of Ernst's painting, so that the photograph functions as a kind of minimal pastiche of the painting, suggesting some kind of parallel between the groups of 1922 and 1928. We could also make a link with another rendez-vous, the celebrated 'Le rendez-vous de chasse' of 1934, in which Mesens figures alongside the rest of the Belgian surrealist group, against a painted studio backdrop (Documents 34 60). Mesens also appears in another group portrait with Van Hecke, in the final issue of Variétés, this time pointedly set against an image of circus clowns. These group photos, I believe, were enormously important, both in affirming group identity, as well as in creating a sense of unity or common purpose, often where no such unity existed - Mesens' taste for scandal and clowning around was not always appreciated by other members of the group, particularly Goemans, with whom he often clashed on the short-lived review Distances that preceded Variétés .

Paris-Brussels: Mesens as Collagist and Publisher

Mesens' activity as a collagist divides into two periods: an early phase from 1924-46 when he produced only a couple of collages, often photo-based, each year; and a late, intense phase from 1954 until his death in 1971, when he regularly produced around forty collages a year. The collages assumed a Dadaist orientation from the outset, inspired both by the early collages of Max Ernst and by the experiments in photography of Man Ray. In one of his earliest collages, The Invasion, 1924, two headless mannequins - one rather taller than the other, suggestive of a parent and child - stand together in a deserted library. The room has been inverted, creating an upside-down world invaded by these acephalous figures and recalls the early work of de Chirico, or the early Dada collages of Raoul Hausmann, which again deploy mannequins and distorted interior spaces. The atmosphere of this image is also recalled in Mesens' poem 'Proclamation', which appeared in the 'Intervention surréaliste' of Documents 34:

Already the wax mannequins invade the libraries

Women walk like wet flags

The insane hand out the image of their mind

At the doors of disused churches (Documents 34 44). [8]

Dada made a quite specific use of collage, characterised by Otlet-Moutoy as being used particularly in opposition to traditional forms of art-making and as marked by a spirit of negativity (Otlet-Moutoy 181-2). Dada collages are notable for their absurdity and their overturning of logic and meaning, mixing incongruous elements to create an alternative reality, often with the addition of some poetic caption or text. Mesens' collages, in their overt combining of contrasting elements from different sources, producing conflicts of scale and logical incoherence, are clearly within the Dada collage tradition of Ernst and Schwitters, rather than in that of the more 'seamless', oneiric visual style more associated with surrealism. Mesens' 1926 collage, The Disconcerting Light (fig. 2), features the eye motif that was to figure so heavily in his work. Here the gigantic eye hovers over a cityscape that recalls the work of Paul Citroën, as a mysterious beam of light flashes out from the pupil into the blackened sky. Mesens used this image in Variétés (June 1929) alongside two more photos, setting similar circular motifs against each other. Brunius, himself a collage maker of some talent, characterises Mesens' method in laying out photos as a kind of collage: "each page", says Brunius, "becomes in fact an undisclosed collage, solely through the play of confrontation" (Brunius n.p.). In this the paired images function either by relations of attraction or of opposition, creating unexpected effects as they meet and collide. Another, less successful, version of the eye motif figures in Mesens' Arrière pensée (1926/7), where the radiant eye is now set against a glass ornament. In fact this image came about by accident in the darkroom of Robert de Smet, when he put a second negative over Mesens' still-life image (Das Innere der Sicht 136). In the layout that he created for Variétés, Mesens juxtaposed the photograph against the image of a spiral staircase by Germaine Krull, thus creating a further layer of meaning in the encounter of the two images.

[photo]

Fig.2 E.L.T. Mesens, The Disconcerting Light (La Lumière déconcertante), 1926.

June 1929 saw the publication of a special issue of Variétés - 'Le Surréalisme en 1929' - which brought about the close collaboration of the Brussels and the Parisian surrealist groups, with Mesens acting as chief intermediary (Dewolf 5-15). Mesens was therefore in a position to include three of his short poems and two of his collages in the collection. The first collage, Je ne pense qu'à vous! , brings together the influence of Man Ray in the form of a photogram of the silhouette of a face, with that of Ernst, in the collaged figures in Edwardian dress and small figures shoeing a horse. Mesens' collages very often contain hidden personal allusions, so that the horse and farrier perhaps allude to Mesens' childhood: Scutenaire relates that Mesens' father's wholesale business deployed a dozen horses and that the family lived near a forge, from which came the sound of bellows and hammers on anvils - the forge later became a garage, and Mesens also set Soupault's poem 'Garage' to music (Scutenaire 23). The grid motif with tiny figures also echoes that in Ernst's 'L'aveugle prédestiné .', one of Ernst's collages for Les malheurs des immortels (1922).

Again, in the second of Mesens' collages, L'instruction obligatoire - a headless female mannequin in a long Edwardian dress, set against a starry backdrop - we discover the persistence of Dada in an image which is almost a pastiche of Ernst's Les ciseaux et leur père, again taken from Les malheurs des immortels. Brunius contends that Ernst, for a quarter of a century, was the biggest obstacle to the development of collage, during which time, he says, "it seemed almost impossible to escape the vertigo of involuntarily imitating him" (Brunius n.p.). Instead of effacing the artist, Brunius argues, collage instead foregrounded him in the form of the "style Max Ernst", where only Ernst was able to escape imitating himself.

Mesens continued to play a key role between Brussels and Paris in a series of collaborations of the early 1930s. In 1933 he founded Éditions Nicolas Flamel, through which he published his Alphabet sourd aveugle, written in hospital in only two days in 1930 (Mesens 1933). The alphabet format is perhaps suggested by Louis Aragon's Dada-style poem 'Suicide' which simply lays out all the letters of the alphabet in the form of a square (Cannibale 4). The frontispiece of Mesens' alphabet is provided by one of his most successful and enigmatic photograms, dating from 1928, and again recalls the early work of Man Ray and Ernst. The image consists of three principal elements set against a backdrop of darkness: an absurd piece of machinery set against an eclipsed circle, suggesting the eye motif; the outline of a crudely drawn hand on a sheet of printed paper, apparently taken from some medical text; and the blurred form of what is perhaps a piece of crumpled paper. The hand, usually traced around as Mesens lacked drawing skills, is another recurring feature of Mesens' work - often in relation to music, keyboards, etc. - as in Mesens' drawing Le Clavecin bien tamponné de Jean Sebastian Bach (Mesens 1944).

Eluard wrote the preface for Mesens' Alphabet, and the Brussels and Paris groups collaborated again in 1933 on Violette Nozières, a collection of poems and visual works in protest at the verdict in the Nozières case, for which Man Ray provided the striking photographic cover. These collaborations between Brussels and Paris culminated in the First International Surrealist Exhibition held at the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels in 1934 - the Minotaure exhibition, hung by Mesens. Breton's lecture given at the closure of the exhibition - 'Qu'est-ce que le surréalisme?' - was subsequently published with Magritte's Le Viol on the cover. Breton in 1934, in response to the question "What is Surrealism?" , responds cannily: "It's the cuckoo's egg left in the nest (the clutch lost) with the complicity of René Magritte. It's relearning to read in the alphabet of stars of E.L.T. Mesens. It's the great lesson in mystery of Paul Nougé." [9] These collaborations were reflected in the composition of Man Ray's 1934 'Surrealist chessboard', which includes both Mesens and Magritte alongside members of the Parisian group - Mesens had been omitted from that of 1929, which featured dreaming surrealists framing Magritte's Je ne vois pas la femme cachée (Hugnet). Finally for 1934, we should also note the 'Intervention surréaliste' in Documents 34 , for which Mesens was editor-in-chief, in close collaboration with Eluard, the contents of which reflected the growing expansion of the surrealist movement, particularly in Belgium, as well as including former Dadaists like Duchamp, Ernst and Tzara.

Mesens quit Belgium in 1938, and during his London period, too, we also find occasional signs of his continuing to revive the Dada spirit, both in his choice of exhibiting artists, and in some of his selections for the London Bulletin (1938-40): Mesens d evoted major shows to Ernst (1938) and to Man Ray (1939), while figures such as Duchamp, Picabia and Schwitters also figured in group exhibitions and in the London Bulletin . Mesens also had what was to prove a decisive encounter with Kurt Schwitters, then an émigré in London. Melly gives a moving account of Schwitters, in March 1947, raging his Dada poem 'Ursonate' in a deserted London gallery, as the BBC sound-recordist quietly leaves. Schwitters and Hausmann proposed that Mesens publish a collection of their jointly-produced Dada poems, but, aware of the minimal public interest in Dada at the time, Mesens' business acumen over-ruled his commitment to Dada and he turned down the proposal (Geurts-Krauss 121). Nonetheless, these late contacts with Dada are seen by Brunius as a key determinant in Mesens' return to collage in the 1950s. Mesens' subversive humour is also well borne out in the tale of the young Melly being sent across the road by Mesens to welcome the pompous new owner of a store selling luxury travelling goods: Melly is instructed to say "The managing director of the London Gallery opposite asked me on his behalf to wish you Good luck, Sir", and then to continue repeating the formula, louder and louder, driving the man into an exasperated rage (Melly 1997: 85).

The Dada joker in Breton's surrealist deck of cards, Mesens was, in Scutenaire's words "during his entire life . a rebel, an element of subversion" (Scutenaire 51). Enthused early in his career by his contact with Paris Dada, Mesens' work and attitudes remained profoundly marked by the impact of Dadaism until the end of his life; that the Dada influence was an enduring one is attested by Mesens' late return to producing collages, in 1954, where the principal influences are again Ernst, Picabia and Schwitters (Vovelle 229-233). Mesens embodied the Dadaist spirit of revolt, overriding ties of religion and nation, and instead affirming a subversive internationalism that made surrealism far more than simply another art movement.

References

Breton, André, Surrealism and Painting, trans. Simon Watson Taylor, Boston: MFA Publications, (1965), 2002.

Brunius, Jacques, 'Rencontres fortuites et concertées', in E.L.T. Mesens: 125 Collages et Objets (exh. cat.), Knokke Le Zoute, 1963, (non-paginated). Cannibale, no.1, 25 April 1920.

Das Innere der Sicht. Surrealistische Fotografie der 30er und 40er Jahre (exh. cat.), Östereichisches Fotoarchiv im Museum Moderner Kunst, 1989.

De Croës, Catherine and Paul Lebeer, 'E.L.T. Mesens: L'homme des liaisons', in L'Art en Belgique. Flandre et Wallonie au XXe siècle (exh. cat.), Paris: Musée de la Ville de Paris, 1991.

Dewolf, Philippe, 'De la mascotte au cadavre', in Variétés. Le Surréalisme en 1929 (reprint), Brussels: Didier Devillez Editeur, 1994.

Documents 34, 'Intervention surréaliste', Bruxelles, Nouvelle série, No.1, June 1934.

Ernst, Max, 'Biographical Notes', in Werner Spies (ed), Max Ernst: A Retrospective (exh. cat.), London: Tate Gallery, 1991.

Geurts-Krauss, Christiane. E.L.T. Mesens. L'Alchimiste méconnu du surréalisme, Bruxelles: Editions Labor et Musée de la littérature, 1998.

Hugnet, Georges, Petite Anthologie poétique du Surréalisme, Paris: Editions Jeanne Bucher, 1934.

Massonet, Stéphane (ed), Dada Terminus. Tristan Tzara - E.L.T. Mesens, correspondance choisie, 1923-1926, Bruxelles : Didier Devillez Editeur, 1997.

Melly, George, 'The W.C. Fields of Surrealism', Sunday Times Colour Magazine, 15 August 1971.

Melly, George, Don't Tell Sybil: An Intimate Memoir of E.L.T. Mesens, London: Heinemann, 1997.

Mesens, E.L.T., Alphabet sourd aveugle, Brussels: Editions Nicolas Flamel, 1933.

Mesens, E.L.T., 'Poème de guerre', Troisième front suivi de pièces détachées, London: London Gallery Editions, 1944.

Mesens, E.L.T., 'I was in marvellous company', Transformaction no.10, Sidmouth, Devon, October 1979.

Osophage (Période), No.1, Brussels, March 1925.

Otlet-Moutoy, Suzanne, 'Les étapes de l'activité créatrice chez E.L.T. Mesens et l'esprit du collage comme aboutissement d'une pensée', Bulletin des Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, nos.1-4 1973.

Picabia, Francis, 391 no.19, Paris, October 1924.

Sauwen, Rik, 'Dada à l'heure belge', L'Art en Belgique. Flandre et Wallonie au XXe siècle (exh. cat.), Paris: Musée de la Ville de Paris, 1991.

Scutenaire, Louis. Mon ami Mesens, Brussels: pub. Scutenaire,1972.

Sylvester, David, Magritte, London: Thames and Hudson (in association with the Menil Foundation), 1992.

Van Hecke, Paul-Gustave, 'Mesens', in E.L.T. Mesens (exh. cat.), Galerie de la Madeleine, Bruxelles, 1966.

Vovelle, José, Le Surréalisme en Belgique, Brussels: André De Rache, 1972.

Willinger, David, Theatrical Gestures of Belgian Modernism, New York: Peter Lang, 2002.

Notes:

[1] "Qu'est-ce que le surréalisme? - C'est réapprendre à lire dans l'alphabet d'étoiles d'E.L.T. Mesens" , André Breton, 1934.

[2] "C'est le plus Bruxellois des citoyens du monde que je connaisse", Paul-Gustave Van Hecke.

[3] "Je suis né le 27 novembre 1903, sans dieu, sans maître, sans roi et sans droits" , E.L.T. Mesens.

[4] "Grâce à l'oeuvre de Satie, voilà ma première revolution personnelle d'accomplie. Adieu, sentimentalités du terroir flamand; adieu, harmonies impressionnistes; adieu, poètes humanitaires à l'eau de rose!", E.L.T. Mesens.

[5] "je crois qu'elle lancera ta revue par un scandale retentissant", Tristan Tzara, February 1925.

[6] "La merde c'est du réalisme, le Surréalisme c'est l'odeur de la merde", Mesens and Magritte.

[7] "Notre bouche est pleine de sang.

Nos oreilles bourdonnent de sang.

Nos yeux s'illuminent de sang." [.]

Paul Nougé, 9 September 1926.

[8] Déjà les mannequins de cire envahissent les bibliothèques

Les femmes marchent comme des drapeaux mouillés

Les fous distribuent l'image de leur esprit

Aux portes des églises désaffectées

E.L.T. Mesens.

[9] "C'est l'oeuf de coucou déposé dans le nid (la couvée perdue) avec la complicité de René Magritte. C'est réapprendre à lire dans l'alphabet d'étoiles d'E.L.T. Mesens. C'est la grande leçon de mystère de Paul Nougé.", André Breton.

About the author

Dr Neil Matheson is Senior Lecturer in Theory and Criticism of Photography at the University of Westminster. He is an art historian specialising in surrealism, and editor of the collection The Sources of Surrealism (Helm, due January 2006). He has written recently on English Surrealism in the journal History of Photography (Summer 2005), and on contemporary German photography in the collection The State of the Real (I.B. Tauris, due December 2005).