Surrealism

On the left hand column you will find information and articles about surrealism. The following overview of surrealism is adapted from Wiki.

Surrealism is a cultural movement that began in the early 1920s (specifically 1924 when Breton published his First Manifesto of Surrealism), and is best known for the visual artworks and writings of the group members.

Surrealist works feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and non sequitur; however, many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost, with the works being an artifact. Leader André Breton was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement.

Surrealism developed out of the Dada activities of World War I and the most important center of the movement was Paris. From the 1920s on, the movement spread around the globe, eventually affecting the visual arts, literature, film, and music, of many countries and languages, as well as political thought and practice, and philosophy and social theory. Below is a painting by Ernst featuring some of the prominent surrealists in 1922.

.jpg)

Max Ernst: At the Rendezvous of Friends 1922

Seated from left to right: Rene Crevel, Max Ernst, Dostoyevsky, Theodore Fraenkel, Jean Paulhan, Benjamin Peret, Johannes T. Baargeld, Robert Desnos. Standing: Philippe Soupault, Jean Arp, Max Morise, Raphael, Paul Eluard, Louis Aragon, Andre Breton, Giorgio de Chirico, Gala Eluard

Founding of the movement

World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and while away from Paris many involved themselves in the Dada movement, believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the terrifying conflict upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-rational anti-art gatherings, performances, writing and art works. After the war when they returned to Paris the Dada activities continued.

During the war Surrealism's soon-to-be leader André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used the psychoanalytic methods of Sigmund Freud with soldiers who were shell-shocked. He also met the young writer Jacques Vaché and felt that he was the spiritual son of writer and 'pataphysician Alfred Jarry, and he came to admire the young writer's anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, "In literature, I am successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most."[1]

Back in Paris, Breton joined in the Dada activities and also started the literary journal Littérature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writing—spontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts—and published the "automatic" writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in Littérature. Breton and Soupault delved deeper into automatism and wrote The Magnetic Fields (Les Champs Magnétiques) in 1919. They continued the automatic writing, gathering more artists and writers into the group, and coming to believe that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than the Dada attack on prevailing values. In addition to Breton, Aragon and Soupault the original Surrealists included Paul Éluard, Benjamin Péret, René Crevel, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Max Morise[2], Marcel Noll, Pierre Naville, Roger Vitrac, Simone Breton, Gala Éluard, Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, Hans Arp, Georges Malkine, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, André Masson, Joan Miró, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Prévert and Yves Tanguy.[3]

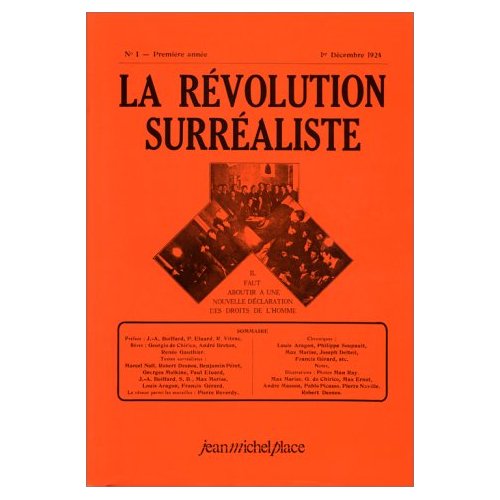

Cover of the first issue of La Révolution surréaliste, December 1924.

As they developed their philosophy they felt that while Dada rejected categories and labels, Surrealism would advocate the idea that ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, but that the sense of their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. They also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such theorists as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse.

Freud's work with free association, dream analysis and the hidden unconscious was of the utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate imagination. However, they embraced idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness or darkness of the mind. (Later the idiosyncratic Salvador Dalí explained it as: "There is only one difference between a madman and me. I am not mad."[4])

The group aimed to revolutionize human experience, including its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects, by freeing people from what they saw as false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed, the true aim of Surrealism is "long live the social revolution, and it alone!" To this goal, at various times surrealists aligned with communism and anarchism.

In 1924 they declared their intents and philosophy with the issuance of the first Surrealist Manifesto. That same year they established the Bureau of Surrealist Research, and began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste.

André Masson. Automatic Drawing. 1924. Ink on paper, 23.5 x 20.6 cm. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Expansion

The movement in the mid-1920s was characterized by meetings in cafes where the Surrealists played collaborative drawing games and discussed the theories of Surrealism. The Surrealists developed a variety of techniques such as automatic drawing.

Breton initially doubted that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement since they appeared to be less malleable and open to chance and automatism. This caution was overcome by the discovery of such techniques as frottage, and decalcomania.

Soon more visual artists joined Surrealism including Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador Dalí, Enrico Donati, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, Méret Oppenheim, Toyen, Grégoire Michonze, and Luis Buñuel. Though Breton admired Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp and courted them to join the movement, they remained peripheral.[5]

More writers also joined, including former Dadaist Tristan Tzara, René Char, Georges Sadoul, André Thirion and Maurice Heine.

In 1925 an autonomous Surrealist group formed in Brussels becoming official in 1926. The group included the musician, poet and artist E.L.T. Mesens, painter and writer René Magritte, Paul Nougé, Marcel Lecomte, Camille Goemans, and André Souris. In 1927 they were joined by the writer Louis Scutenaire. They corresponded regularly with the Paris group, and in 1927 both Goemans and Magritte moved to Paris and frequented Breton's circle.[3]

The artists, with their roots in Dada and Cubism, the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky and Expressionism, and Post-Impressionism, also reached to older "bloodlines" such as Hieronymus Bosch, and the so-called primitive and naive arts.

André Masson's automatic drawings of 1923, are often used as the point of the acceptance of visual arts and the break from Dada, since they reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind. Another example is Alberto Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from preclassical sculpture.

However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen)[6] with The Kiss (Le Baiser)[7] from 1927 by Ernst. The first is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, whereas the second presents an erotic act openly and directly. In the second the influence of Miró and the drawing style of Picasso is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and colour, where as the first takes a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Giorgio de Chirico The Red Tower (La Tour Rouge) (1913).

Giorgio de Chirico, and his previous development of Metaphysical art, was one of the important joining figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted an unornamented depictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. The Red Tower (La tour rouge) from 1913 shows the stark colour contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 The Nostalgia of the Poet (La Nostalgie du poete)[8] has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief defies conventional explanation. He was also a writer, and his novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax and grammar designed to create a particular atmosphere and frame around its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballets Russes, would create a decorative form of visual Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two artists who would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Salvador Dalí and Magritte. He would, however, leave the Surrealist group in 1928.

In 1924, Miro and Masson applied Surrealism theory to painting explicitly leading to the La Peinture Surrealiste exhibition of 1925. La Peinture Surrealiste exhibition was the first ever Surrealist exhibition at Gallerie Pierre in Paris, and displayed works by Masson, Man Ray, Klee, Miró, and others. The show confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), and techniques from Dada, such as photomontage, were used. The following year, on March 26, 1926 Galerie Surréaliste opened with an exhibition by Man Ray.

Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s.

René Magritte "This is not a pipe." The Treachery Of Images 1928-9

Writing continues

The first Surrealist work, according to leader Breton, was Magnetic Fields (Les Champs Magnétiques) (May–June 1919). Litérature contained automatist works and accounts of dreams. The magazine and the portfolio both showed their disdain for literal meanings given to objects and focused rather on the undertones, the poetic undercurrents present. Not only did they give emphasis to the poetic undercurrents, but also to the connotations and the overtones which "exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images."

Because Surrealist writers seldom, if ever, appear to organize their thoughts and the images they present, some people find much of their work difficult to parse. This notion however is a superficial comprehension, prompted no doubt by Breton's initial emphasis on automatic writing as the main route toward a higher reality. But — as in Breton's case itself — much of what is presented as purely automatic is actually edited and very "thought out". Breton himself later admitted that automatic writing's centrality had been overstated, and other elements were introduced, especially as the growing involvement of visual artists in the movement forced the issue, since automatic painting required a rather more strenuous set of approaches. Thus such elements as collage were introduced, arising partly from an ideal of startling juxtapositions as revealed in Pierre Reverdy's poetry. And — as in Magritte's case (where there is no obvious recourse to either automatic techniques or collage) the very notion of convulsive joining became a tool for revelation in and of itself. Surrealism was meant to be always in flux — to be more modern than modern — and so it was natural there should be a rapid shuffling of the philosophy as new challenges arose.

Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, known by his pseudonym "Le Comte de Lautréamont" and for the line "beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella", and Arthur Rimbaud, two late 19th century writers believed to be the precursors of Surrealism.

Examples of Surrealist literature are Crevel's Mr. Knife Miss Fork (1931), Aragon's Irene's Cunt (1927), Breton's Sur la route de San Romano (1948), Péret's Death to the Pigs (1929), and Artaud's Le Pese-Nerfs (1926).

La Révolution surréaliste continued publication into 1929 with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but also included reproductions of art, among them works by de Chirico, Ernst, Masson and Man Ray. Other works included books, poems, pamphlets, automatic texts and theoretical tracts.